Secrets of the Crypt

Tue, 11 Sep 2012 12:37:00 BST

Dr Stefano Vanin’s forensic expertise is used to learn lessons from the extraordinary Mummies of Roccapelago

ON the desk of Dr Stefano Vanin (pictured right) at the University of Huddersfield are a number of bags and jars that appear to contain just dust and dirt. Closer examination shows that mingled among the contents are the wings, limbs and other tiny vestiges of insects.

ON the desk of Dr Stefano Vanin (pictured right) at the University of Huddersfield are a number of bags and jars that appear to contain just dust and dirt. Closer examination shows that mingled among the contents are the wings, limbs and other tiny vestiges of insects.

And these will help Dr Vanin unlock secrets from one of the most exciting and extraordinary archaeological finds of the past 100 years – a huge number of perfectly mummified bodies in the sealed and forgotten crypt of an obscure Italian church.

Much of their clothing was intact and the corpses were still clutching religious artefacts or the tools of their trade in life. The bodies had also been infested – centuries ago – by legions of insects. And that is how the University of Huddersfield’s Dr Vanin – Italian-born himself and one of the world’s leading forensic entomologists – became a key member of the team researching the life and death of the Mummies of Roccapelago.

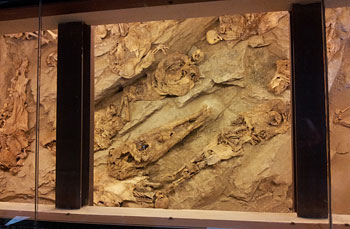

The church of the Conversion of St Paul in Roccapelago di Pievepelago, in the Italian Apennine mountains, was built in the fifteenth century on the site of an abandoned hilltop castle. A chamber that had been used as a cannon enclosure became the church’s crypt and between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries it was the common tomb for some 281 inhabitants of the tiny town. (as seen below)

People of all ages and all stations in life were deposited in the crypt which, when it reached its capacity after several centuries, was sealed and forgotten. Meanwhile, the unusual microclimate of Roccapelago resulted in a process of natural mummification, so that some 60 of the bodies were perfectly preserved.

The remarkable discovery

In late 2010, restoration work began at the church. The crypt was reopened and the extraordinary discovery was made. The Mummies of Roccapelago rapidly became famous.

In late 2010, restoration work began at the church. The crypt was reopened and the extraordinary discovery was made. The Mummies of Roccapelago rapidly became famous.

A museum displaying a large number of the mummies and a special display at the church itself (pictured left) have been major summer tourist attractions in Italy, while a wide range of experts in a number of academic disciplines have collaborated, so that the discovery of the bodies, their clothes and their belongings will yield a massive amount of historical, social and scientific information.

Dr Vanin, whose detailed knowledge of insect activity in corpses has led to involvement in high-profile criminal and archaeological case studies, is one of the team of experts working on the project. He is due to report on his findings so far at an academic conference in late September.

Large numbers of mites and insect cocoons remained on the mummified bodies. Dr Vanin has so far examined some 30 of the corpses and he retrieved detritus that he brought back to the University of Huddersfield, where he can subject the insect remains to detailed analysis.

Defining the time of death

An important contribution that he can make to an understanding of the life and death of the inhabitants of Roccapelago is that he can deduce the seasons in which the mummified bodies died. For example, a winter death would have resulted in insect infestation some time after the corpse had begun to decompose, whereas flies would have colonised the corpse much earlier during the warmer months.

By establishing the seasonality of death, the realities of life hundreds of years ago in a remote Italian village will become much more clear.

Born in Treviso, Dr Vanin came to the University of Huddersfield as a Senior Lecturer in Forensic Biology in 2011. His previous post was at the University of Padua. His wide-ranging research portfolio contains previous work on mummified bodies, including that of a First World War soldier and an ancient Egyptian mummy.