Peace process?

Thu, 26 Jul 2012 16:11:00 BST

Colombian researcher investigates signs of hope in his country's armed conflict

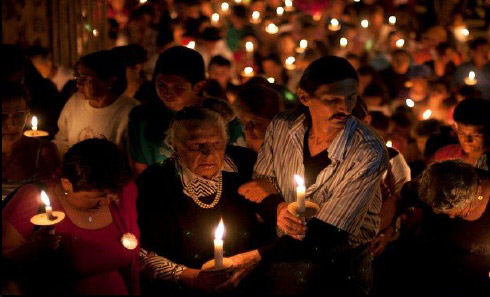

A March of Light by victims of Colombia's armed conflict

THE world’s longest armed conflict has claimed ten million lives and shattered countless families. Is there a prospect of peace in Colombia? University of Huddersfield PhD student Camilo Tamayo Gomez (pictured), who has witnessed killings and known some of the kidnap victims, is conducting research into the peace efforts of various non-government organisations in the country.

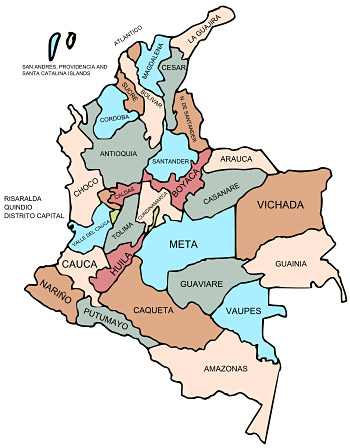

He will soon return to his native country for a further two months’ research in the region of Eastern Antioquia, home to a disproportionately high 42 per cent of the victims of Colombia’s 50-year conflict, fought out between the government, groups of armed insurgents and paramilitary organisations, with innocent civilians making up 94 per cent of those slain.

The location and the natural resources of Eastern Antioquia have made it a strategic corridor for drug and gun running and it has produced some of the most significant of Colombia’s paramilitary leaders.

It is a risky place to carry out research, but Camilo, aged 34, knows the area well.

“My protection is that I have been working with these people for a long time,” he says.

Before he relocated to the UK for postgraduate study, Camilo worked with non-governmental organisations and the UN in the field of communication and human rights and has also formed a link with the Association of Organised Women of Eastern Antioquia, which has played a central part in new strategies to bring peace to Colombia.

The process is dubbed Communicative Citizenship and it is the basis of Camilo’s PhD project at the University of Huddersfield, where he is based in the School of Human and Health Sciences.

Having completed a Masters degree in political philosophy in the UK, he was awarded a Sir John Ramsden Scholarship, which brought him to Huddersfield to work on a thesis that he hopes will help the Colombian government develop policies that may lead to peace.

Camilo, who is from Bogota, the capital of Colombia, has personally witnessed seven massacres.

But this is not so exceptional. Every Colombian has been affected by the armed conflict, says Camilo. He explains that organisations such as the Association of Organised Women of Eastern Antioquia are adopting strategies which aim to construct a new kind of citizenship, reclaim human rights and construct a narrative of the conflict that could lead to new peace policies.

Strategies include a March of Light, taking place in 23 towns of Eastern Antioquia, which see large numbers of people take to the streets with a candle in memory of a victim. Also there are Walls of Memory – enormous montages of photographs of murdered citizens.

The fact that women are playing a lead role in these protests is significant – 61 per cent of the victims of the armed conflict have been female.

“In the logic of war, if you kill women it sends out a very powerful message in order to destabilise a region,” says Camilo.

But how can movements such as Association of Organised Women of Eastern Antioquia and protests such as the March of Light make an impact on such an entrenched conflict?

“These groups of women are creating another narrative,” explains Camilo. “For the Colombian government it is not an armed conflict, it is a terrorist threat. But these groups of women have begun to construct another point of view, claiming that it is military conflict.”

If this narrative prevails, then external attitudes to the conflict could alter.

“For example, the USA supports the Colombian government in the basis that it is a terrorist conflict. If it is redefined as an armed conflict, then the United Nations could put pressure on the government to behave differently.”

This could lead to greater respect for human rights and support for civil associations. Camilo can foresee that within ten years, social action and protest will lead to a peace process involving government, guerrillas and the paramilitaries. And he hopes that his research, analysis and outputs – including a recent award winning conference paper (see http://www.hud.ac.uk/news/researchnews/ciceabraceforhuddersfield.php) – will play some part in the process of change.

Meanwhile, Colombia is best understood as a Jekyll and Hyde country, he says.

“There is a good face to Colombia – the people, the natural resources. The main cities are good places to be. But if you go to rural areas, the borders or places like Eastern Antioquia, then you see the bad face.”

For more on the issues visit: