Never too old to learn

Tue, 19 Jun 2012 16:16:00 BST

“...Britain would be better off if its population was better educated...”

LIFELONG learning and the social factors that inhibit or prevent people from continuing with their education have been important strands of Professor Lyn Tett’s work and research. It has roots in her own experience as an adult returner to education.

The University of Huddersfield’s track record for research in fields such as youth and community work is one of the factors that attracted Lyn Tett (pictured) to take up her new post as its Professor of Community Education – despite a 500-mile round trip.

She is Bristol-born, but most of her life and career have been spent in Scotland, where she has held a number of key posts in the fields of adult and community education and she is an Emeritus Professor of the University of Edinburgh.

She remains in Scotland, coming to Huddersfield one week-per month for her part-time post. But she is looking forward to developing fruitful research partnerships with her new colleagues in Yorkshire.

“About ten years ago I was the external examiner for the University of Huddersfield’s degree course in youth and community work and I have kept in touch,” she says. “Huddersfield has a very strong reputation in youth and community work and in adult education.”

While her children were young she was a part-time student of psychology at the Open University. She then became an adult education development officer for Argyll and Bute Council’s community education service, before moving to Edinburgh as deputy director of the Scottish Community Education Council responsible for training and adult education.

She then joined Moray House Institute of Education as the Director of Community Education, whilst studying part-time for an MSc in Community Education. In 2002 she became the University of Edinburgh’s Professor of Community Education and Lifelong Learning.

Broad arguments

She advances two broad arguments for the encouragement of adult participation in education.

“In general the people that did best at school tend to carry on benefiting from education. They get the qualifications, go to university and get better jobs. So there is a social justice argument in favour of helping those who haven’t benefitted earlier to gain access to education later in life,” says Professor Tett.

And there is also an economic argument, she adds. An advanced society such as Britain would be better off as whole if its population was better educated.

“Unequal societies have more problems, including poor health and poor literacy levels. The more equal a society is, then the less you are likely to have these kinds of issues.”

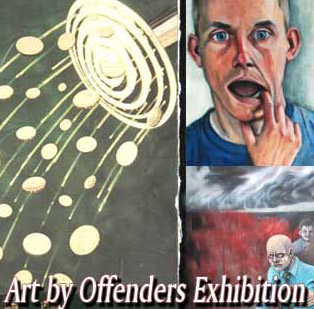

A recent area of research for Professor Tett has been a project examining the impact made on the literacy skills of prisoners after they have been involved in arts projects.

“If you use things like musical activity, drama or photography in order to help prisoners express themselves verbally or in writing, then it has a very positive impact on their literacy skills, their feelings of self-esteem and their confidence.”