Ulster Loyalist perspectives on the IRA and Irish Republicanism

Wed, 18 May 2016 11:08:00 BST

Professor Jim McAuley talks to members and former members of Loyalist paramilitary groups to find out what they really think of the Republican counterparts

DESPITE occasional eruptions of violence and flashes of tension, the peace process in Northern Ireland has held. But what do today’s Loyalists really think of their Irish Republican counterparts?

DESPITE occasional eruptions of violence and flashes of tension, the peace process in Northern Ireland has held. But what do today’s Loyalists really think of their Irish Republican counterparts?

The University of Huddersfield’s Professor Jim McAuley – (pictured right) a leading authority on the history and politics of the province – has found out, by talking to members and former members of paramilitary groups, including some who have served jail terms.

He has discovered that while there is little support for a return to open conflict, and there is a measure of respect for former foes, some loyalist communities are feeling marginalised and that in place of violence there is now seen to be a “culture war”.

In his latest article – co-written with Professor Neil Ferguson of Liverpool Hope University – Professor McAuley concludes that many loyalists believe that “republicans are all too intent to try and dispel the legitimacy of both loyalist culture and identity. Because of this there is a sense in the unionist/loyalist community that they are constantly being pursued by republicans who cannot look beyond their passion for an Ireland that never existed”.

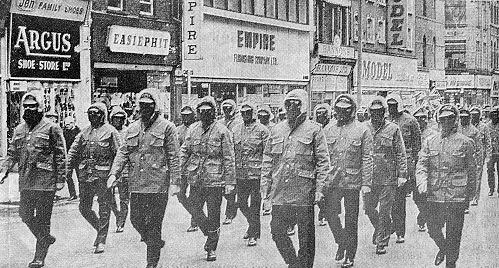

◄ Loyalist paramilitaries march against the Sunningdale power-sharing agreement in 1974

The article is titled ‘Us’ and ‘Them’: Ulster Loyalist Perspectives on the IRA and Irish Republicanism. It appears in a special edition of the journal Terrorism and Political Violence that marks 100 years of Irish Republican violence, since the Easter Rising of 1916. The year 2016 also marks the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, and Professor McAuley pinpoints the heavy death toll among soldiers of the 36th (Ulster) Division as an important factor in the formation of loyalist identity.

The new article draws on interviews that the authors conducted with members and former members of the Ulster Volunteer Force, Ulster Defence Association, Red Hand Commando, Ulster Political Research Group, and the Progressive Unionist Party. The article explains the genesis of the term “loyalist” and the working class connotations that led “more advantaged” unionists to disassociate themselves with it.

A thread running through the article is the analysis that “loyalism emerged from and remains, directed by fear and dread of the Other”. But although problems remain, “loyalist commitment to a transformed society has endured, albeit at times in an imperfect way”.

Some loyalists, including former prisoners, express “a degree of veneration and respect mixed with antagonism and resistance” towards their republican counterparts.

One UDA member told the researchers how “you can’t fight an enemy and not start to admire them because the minute you start to take them for granted, you’re a dead man. I always held them in high esteem that way”. He also stated that he admired his opponents’ commitment and courage, although “when they talked about the 100-year war we used to laugh”.

One UDA member told the researchers how “you can’t fight an enemy and not start to admire them because the minute you start to take them for granted, you’re a dead man. I always held them in high esteem that way”. He also stated that he admired his opponents’ commitment and courage, although “when they talked about the 100-year war we used to laugh”.

There was acknowledgment from a UPRG member that Sinn Féin – despite “the lies, the spin they’ve put on things” – are a grassroots party that works with people on bread and butter issues.

In their conclusion, Professor McAuley and Professor Ferguson (pictured right) write that:

“The relationship between contemporary loyalism and republicanism is more complex than many would imagine. The focus remains on the collective memory of the conflict, the narrative of which remains prejudiced and one-sided. When such a narrative is adopted in the collective memory, it plays a major role in the course of a conflict, insofar as it shapes the reactions of each party positively towards itself and negatively towards its rival. Past experiences of violence are passed on in collective memory, enhanced by the continued physical and social separation of both communities in post-conflict Northern Ireland.”