Mad dogs and Englishmen – mental health and the rulers of the Raj

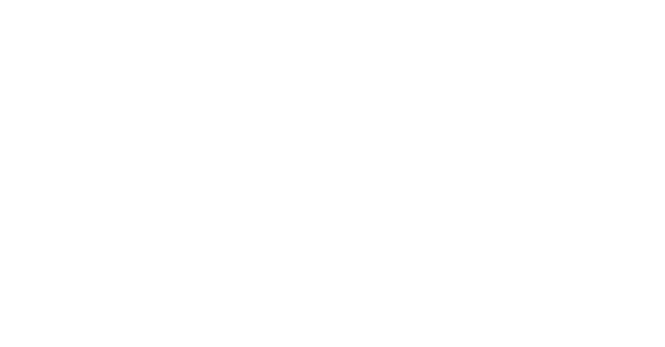

Pictured is the Central Institute of Psychiatry, in Ranchi, India, which first opened in 1918 as the European Mental Hospital.

Pictured is the Central Institute of Psychiatry, in Ranchi, India, which first opened in 1918 as the European Mental Hospital.

Thu, 12 May 2016 13:11:00 BST

Research shows high level of mental health issues of the men and women who went out to rule the Raj in India

THE British Empire could be bad for the mental health of the men and women who went out to rule the Raj. After poring over pre-1947 asylum records that survive in India, University of Huddersfield researcher Mike Young has pinpointed factors that meant some Europeans just could not cope with the ‘Imperial experience’.

THE British Empire could be bad for the mental health of the men and women who went out to rule the Raj. After poring over pre-1947 asylum records that survive in India, University of Huddersfield researcher Mike Young has pinpointed factors that meant some Europeans just could not cope with the ‘Imperial experience’.

A retired social worker and senior manager of mental health services in West Yorkshire, Mr Young has developed a fascination for India and for history. He combines his interests and professional background in a PhD project – now in its closing stages – dealing with the mental health of the British in Colonial India between 1914 and 1947, when the vast country gained its independence.

“I am finding that some British people could not cope with Empire and with being imperial ambassadors,” said Mr Young. “They were on show all the time as an allegedly superior race, which of course they weren’t. Some people just could not handle this and it led to a breakdown.”

Bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia – then termed dementia praecox – were among the conditions that Mr Young has encountered in records that survive in the archives of what is now the Central Institute of Psychiatry, in Ranchi, 250 miles north west of Kolkata. First opened in 1918, it was originally named the European Mental Hospital and was reserved strictly for white patients, plus people categorised as Anglo-Indian.

“It was geared at British or European people to give them the kind of service they might have had back home, but it was quite blatantly racist,” said Mr Young, who has paid two research visits to Ranchi.

Colonials struggled to cope

The European Mental Hospital had a capacity of about 200 patients and Mr Young (pictured left) has been able to analyse a good sample of their records, including the treatments that they received. These were often based on the most advanced European developments, and included the use of hydro-therapy – lengthy immersion in warm baths. It often proved effective.

The European Mental Hospital had a capacity of about 200 patients and Mr Young (pictured left) has been able to analyse a good sample of their records, including the treatments that they received. These were often based on the most advanced European developments, and included the use of hydro-therapy – lengthy immersion in warm baths. It often proved effective.

A high proportion of the records seen by Mr Young were for female patients, often the wives of British soldiers or civil servants.

Isolation is a factor that can put people at risk of mental illness, said Mr Young, and being part of a tiny minority – albeit a privileged one – In India resulted in exceptional isolation for Britons. Extreme heat – inescapable before the coming of air-conditioning – was also a factor

“The British had to maintain a certain prestige and standards. They were surrounded by tens of thousands of Indians, but most Britons had little do with them because of racism and a wish to be seen apart, as the rulers.

“Some people thrived on this. But some just couldn’t cope with the weather or the isolation.”

The British in India only ever amounted to about half a per cent of its 300 million population, so there was a constant fear of an uprising, or a recurrence of the Mutiny or Great Rebellion of 1857. This dread was another factor that caused mental health problems for some Britons.

Interest in the sub-continent

Interest in the sub-continent

Mike Young’s PhD at the University of Huddersfield is supervised by Senior Lecturer Dr Rob Ellis, who has a specialisation in the history of mental health care.

Before turning to historical research, Mr Young concluded his earlier career as Professional Social Care Lead for Mental Health at Kirklees Council Social Services. He was also a director of the district’s NHS Mental Health Trust and was one of the team based at the former Storthes Hall Hospital in Huddersfield in its final years before closure in 1992. It is now the site of University of Huddersfield student accommodation.

Earlier in his career, he worked extensively with Pakistani and Indian communities in Calderdale and Kirklees. This led to an interest in the sub-continent and its people, with fact-finding visits to mental hospitals in Gujarat. The seeds were also sown for his current research project, during which Mr Young has also made several conference presentations outlining his findings about the mental health issues that confronted the rulers of the Raj.