Hellfire sermons! The power behind the pulpit in the Pennines

Fri, 04 Mar 2016 14:22:00 GMT

Salvation or damnation? Historian explores 400-year-old documents, records and sermons to find the preaching power of the Pennine chapels in the late Elizabethan and early Stuart periods

A UNIVERSITY of Huddersfield historian has measured the power of the pulpit in the England of 400 years ago. For worshippers, their reaction to sermons could mean the difference between an afterlife of bliss or an eternity of hellish torment.

A UNIVERSITY of Huddersfield historian has measured the power of the pulpit in the England of 400 years ago. For worshippers, their reaction to sermons could mean the difference between an afterlife of bliss or an eternity of hellish torment.

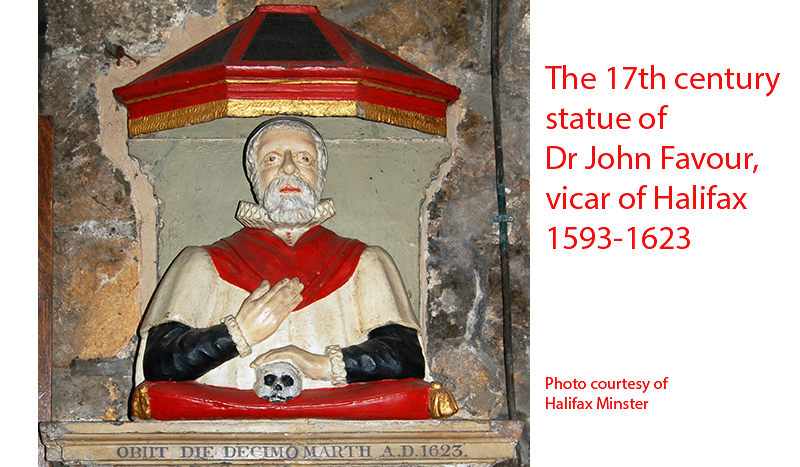

By the 1580s, England was established as a Protestant nation. The word of God, as expounded from the pulpit, had gained increased significance and some communities would raise funds to restore chapels and then send out talent scouts to find the most potent preachers.

“The sermon was a feature of religion before Protestantism, but the big difference is that after the Reformation it becomes the means of salvation,” said Dr Margaret Bullett, who has completed a highly-praised thesis on the importance of preaching in Pennine chapels and churches between 1580 and 1660. It was the Calvinist doctrine of pre-destination that made the difference, she explained.

“Whereas before you could earn your way into heaven by good works and penance, after the Reformation the doctrine was that you are either saved or you are damned, and your reaction to preaching of the Word will show you whether or not you are one of the Elect.”

Dr Bullett has used a wide range of sources, including parish records, court material, ballads and more than 50 sermons to develop a new picture of popular religion in the Pennines in the late Elizabethan and early Stuart periods.

Dr Bullett has used a wide range of sources, including parish records, court material, ballads and more than 50 sermons to develop a new picture of popular religion in the Pennines in the late Elizabethan and early Stuart periods.

She has used this material to challenge the view held by many historians that “godly” people amounted to only a small proportion of the population.

“I have shown that a wider cross section of the population could be involved with preaching,” she said. “For example, there were collections to rebuild chapels and there was fund-raising to employ preachers.

“A very wide section of the population could be involved, even down to people just donating a few pence. They are simultaneously showing that they belong to that local community and taking part in godly action. I have argued that that the divide between the godly and everybody else is more blurred than is usually thought to be the case.”

“Doctoral theses aren’t normally this good”

Dr Bullett’s thesis – supervised at the University of Huddersfield by Head of History Dr Sarah Bastow and Dr Pat Cullum – is entitled Post Reformation Preaching in the Pennines: Space, Identity and Affectivity. The external examiner for her PhD was Professor Alec Ryrie, a leading church historian who specialises in the Reformation era. He was so enthusiastic about Dr Bullett’s findings that he took the unusual step of blogging about her thesis.

“Doctoral theses aren’t normally this good,” he writes, praising its “real scholarly substance.”

Professor Ryrie continues:

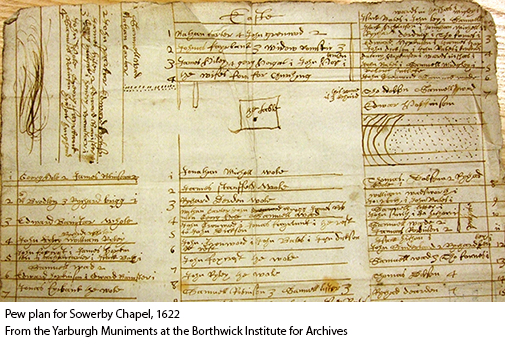

The most exciting innovation … is her use of financial records to unlock a whole new set of data about popular participation in local religion. It wouldn’t be possible to do this for the heavily-parished south of England, but in the North, huge parishes with multiple chapelries required and allowed much greater lay involvement. So when she shows us communities arriving at a consensus that they intend to levy a rate, or simply mobilising huge numbers of small donations, to pay for visiting ‘godly’ preachers; when we see them building or rebuilding their chapels with architecture which prioritises preaching, dedicating their pew rents to the support of the godly ministry, and pricing the pews so that the ones nearest to the pulpit…are the most expensive – it’s hard to avoid the once-unthinkable conclusion that there is some real popular Calvinism happening in the Yorkshire dales.

Dr Bullett is a former Environment Agency water resources officer who turned to history study – part-time to begin with – securing a BA and Master’s at the University of Huddersfield, during which she developed a fascination for religious identities during the Elizabethan and Stuart periods. She expanded her researches for the successful PhD. Now she intends to build up a national picture.

Dr Bullett is a former Environment Agency water resources officer who turned to history study – part-time to begin with – securing a BA and Master’s at the University of Huddersfield, during which she developed a fascination for religious identities during the Elizabethan and Stuart periods. She expanded her researches for the successful PhD. Now she intends to build up a national picture.

“It won’t be the same everywhere, and particularly not in the more settled areas of East Anglia and the South East. But I plan to look in the Midlands and the South West to see if there are any similar patterns of support for preaching that also played a role in the redefining of the parish community after the Reformation.”