£400k project researching the redoubtable reformer Emily Hobhouse

Thu, 21 Jul 2016 14:42:00 BST

Dr Rebecca Gill joins three other universities for the The Emily Hobhouse Letters project backed by the AHRC

THE formidable Emily Hobhouse earned obloquy in her native Britain when she fought tirelessly on behalf of women and children herded into concentration camps during the South African War (1899-1902). But she was much more than a single issue campaigner.

THE formidable Emily Hobhouse earned obloquy in her native Britain when she fought tirelessly on behalf of women and children herded into concentration camps during the South African War (1899-1902). But she was much more than a single issue campaigner.

She also agitated for female suffrage, became closely involved with humanitarian relief work during the First World War, helped to launch the Save the Children Fund, and made an attempt to develop an arts and crafts movement in South Africa as a way to unite the country. She formed friendships with major figures such as India’s Mahatma Gandhi and had no qualms about confronting British prime ministers.

Now, the University of Huddersfield’s Dr Rebecca Gill – who specialises in the history of humanitarian organisations – is part of a £400,000, three-year project that will analyse Hobhouse’s voluminous correspondence and present a new, more rounded view of a figure who played a distinctive part in many of the forces that shaped the world during the early 20th century.

Dr Gill teams up with Dr Helen Dampier, of Leeds Beckett University, and Dr Kate Law, of the University of the Free State in South Africa for a project backed by the Arts and Humanities Research Council titled The Emily Hobhouse Letters. Their research will lead to a book and to a touring exhibition that will be mounted in UK and South African venues.

Hobhouse – who lived from 1860 to 1926 – was dedicated to liberal causes and an opponent of the South African War, which was fought between 1899 and 1902. When she took up the cause of South African civilians interned in British camps she was widely regarded as a traitor in her home country. But she was undeterred in the face of hostility when, for example, she came to Huddersfield in 1901, hosted by local Quakers, and gave a talk on the treatment of Boer women.

Hobhouse – who lived from 1860 to 1926 – was dedicated to liberal causes and an opponent of the South African War, which was fought between 1899 and 1902. When she took up the cause of South African civilians interned in British camps she was widely regarded as a traitor in her home country. But she was undeterred in the face of hostility when, for example, she came to Huddersfield in 1901, hosted by local Quakers, and gave a talk on the treatment of Boer women.

She also refused to be intimidated by men in power.

“She is one of these formidable early 20th century women who had that sense of entitlement to scold!” said Dr Gill. “She didn’t think twice about writing to Campbell-Bannerman, when he became the Liberal Prime Minister, as part of her campaign for Britain to give South Africa its independence.”

◄ Dr Rebecca Gill

◄ Dr Rebecca Gill

Most of the correspondence at the heart of the Emily Hobhouse Project is archived in South Africa – where Hobhouse lived for several years – and an important goal is to place the country in an international context. Dr Gill will pay several research visits to South Africa and a special conference is to take place at the University of the Free State towards the end of the project. Also, a partnership has been formed with the War Museum in Bloemfontein, the town where Emily’s ashes were taken after she died in London in June 1926.

“South African history has been rather parochial, because of the apartheid years,” said Dr Gill. “We are trying to show how South Africa is part of an international story, and how figures like Hobhouse and Jan Smuts were involved in setting up formal international organisations. We will work in the archives of the Save the Children Fund and the League of Nations in Geneva to try and follow this story back to Europe and try to show how South Africa’s politicians and activists contributed to the foundation of the new international order.”

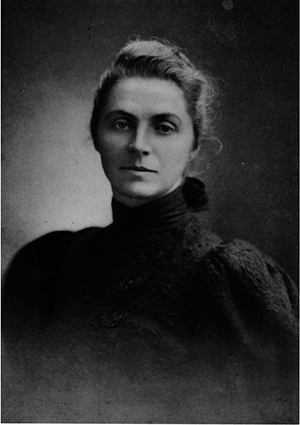

► Mahatma Gandhi pictured in 1902 in South Africa

► Mahatma Gandhi pictured in 1902 in South Africa

The research has only recently started, but already there has been an unexpected finding. While dwelling in South Africa in the early 1900s, Emily Hobhouse ran a weaving and spinning school as part of her aim to unite Boers and Britons and create a self-sufficient arts and crafts culture in the country. At this period she befriended Mahatma Gandhi, who would later follow a similar course in India.

Artefacts from Emily Hobhouse’s craft enterprise – including designs for lace – have been discovered, and they will contribute to the research project.

“The objective of the school was to make sure that women of respectable birth in South Africa didn’t slip down the class ladder, and to re-equip homes that had been ruined in the war. It was also about giving South Africa a sense of identity,” said Dr Gill.

One issue that the research team must confront is Emily Hobhouse’s attitude to black Africans.

“This is a big question for us,” said Dr Gill. “Emily was interested in peace and reconciliation, but the priority was to build peaceful relations between the white populations. She doesn’t talk about native rights.

“The charitable view is that she prioritised good relations between whites because only then would you be able to raise questions about the black population. Then again she was embedded in circles with Smuts and Boer leaders who were either overtly segregationist or segregationists by default. We are trying to get to grips with her attitude.”

- Read more about the Emily Hobhouse Letters project at its website.