How the Festival of Britain created a new York!

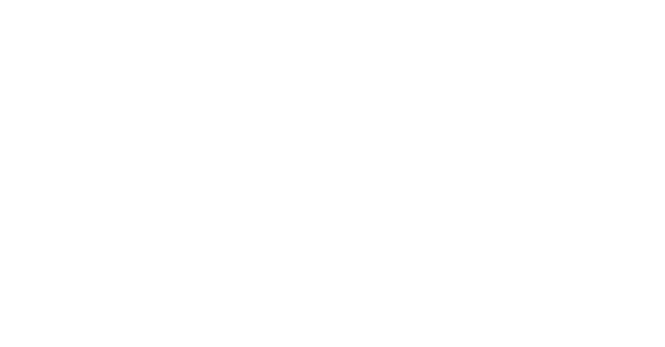

Pictured above left: The trendy Festival Flats of Fishergate in York were built in the aftermath of World War Two to celebrate the 1951 Festival of Britain. Below left: One of the modern living rooms in the Festival Flats. Above right: 1951 Festival of Britain poster.

Pictured above left: The trendy Festival Flats of Fishergate in York were built in the aftermath of World War Two to celebrate the 1951 Festival of Britain. Below left: One of the modern living rooms in the Festival Flats. Above right: 1951 Festival of Britain poster.

Mon, 11 Jan 2016 15:00:00 GMT

University researcher uncovers how post-war planners aimed to transform an ancient city

YORK was famous for its Roman ruins and medieval buildings. But in the aftermath of World War Two, its political leaders wanted to turn it into a city of the future. Now a University of Huddersfield lecturer has been researching attempts to transform the image of York during the 1951 Festival of Britain.

YORK was famous for its Roman ruins and medieval buildings. But in the aftermath of World War Two, its political leaders wanted to turn it into a city of the future. Now a University of Huddersfield lecturer has been researching attempts to transform the image of York during the 1951 Festival of Britain.

In doing so, Caterina Benincasa-Sharman (pictured), who is a Senior Lecturer in Historical and Theoretical Studies in the School of Art, Design and Architecture, is one of a new wave of researchers paying greater attention to a neglected period in British architectural history.

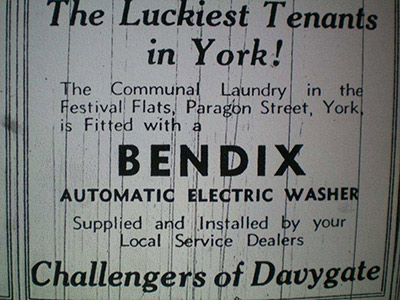

◄ A sign stating the tenants of the Festival Flats were the luckiest in York because it had a communal Bendix Automatic Electric Washer.

◄ A sign stating the tenants of the Festival Flats were the luckiest in York because it had a communal Bendix Automatic Electric Washer.

York has proved to be a fascinating case study that will be a crucial element of a doctoral thesis that Caterina is now completing.

The Festival of Britain – intended as a tonic for the nation after years of post-war austerity – is often regarded as essentially a London event. But it was marked throughout the nation and Caterina has uncovered large quantities of material showing how the Festival was celebrated in Northern cities.

She decided to focus on Liverpool and York and one of her most recent research outputs was a presentation at a Stirling University conference entitled Reading Architecture Across the Arts and Humanities. Her paper was Architectural Nous: How York Wrote its Identity Through Architecture During the 1951 Festival of Britain.

It was based on the city council’s strategy for the Festival. It carried out restorations of historic buildings such as the Art Gallery and Assembly Rooms; and it staged arts events in buildings such as the Minster, to show that they still had a role in the modern world.

►The Festival Flats in Fishergate are still in good condition today.

But councillors also decided to commission leading architects to build new and modern blocks of public housing.

“They saw this as a way of proving that York was looking to the future, that it could be world-leading in its architecture and become a model for other places,” said Caterina.

Two blocks were built. One was inside the city walls at Castlegate (pictured left), designed in a mixture of neo-renaissance, neo-Georgian and modernist styles by Robert Atkinson. Just outside the city walls there was a more overtly modernist structure outside the city walls at Fishergate, designed by the London practice Topliss and Meadow. As a British compromise with modernism, these flats were built in brick.

Two blocks were built. One was inside the city walls at Castlegate (pictured left), designed in a mixture of neo-renaissance, neo-Georgian and modernist styles by Robert Atkinson. Just outside the city walls there was a more overtly modernist structure outside the city walls at Fishergate, designed by the London practice Topliss and Meadow. As a British compromise with modernism, these flats were built in brick.

Both blocks of flats are still public housing and in good condition, said Caterina. Now her research into the genesis of the buildings, a part of York’s multi-stranded approach to the Festival of Britain, will feed into her thesis, as it has done to her lectures in the history of architecture.

Caterina believes that immediate post-war architecture is a subject that has been under-researched and her work on York in the Festival of Britain has helped her to enter the field.