Lego Serious Play aids history undergrads to express in words

Wed, 24 Jun 2015 15:23:00 BST

“...after a session with the Lego, first-year undergraduates can be much more ready, willing and able to develop and express their ideas in words...”

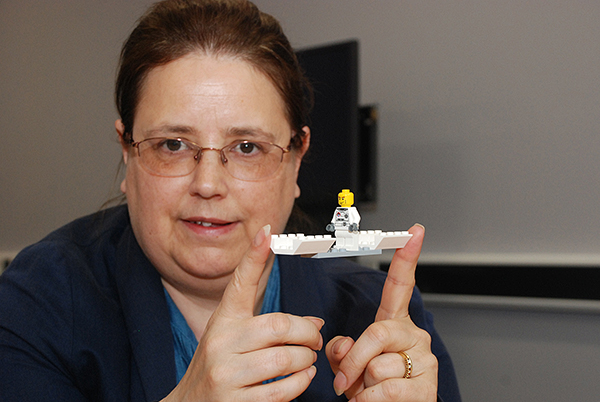

WHEN University of Huddersfield history lecturer Dr Pat Cullum needs new students to grapple with some tricky intellectual concepts, one solution is to get out a Lego set.

WHEN University of Huddersfield history lecturer Dr Pat Cullum needs new students to grapple with some tricky intellectual concepts, one solution is to get out a Lego set.

After a session spent building structures with the famous plastic bricks, first-year undergraduates can be much more ready, willing and able to develop and express their ideas in words, says Dr Cullum.

She has been so encouraged by her experiments in using Lego as an improbable teaching strategy in a subject such as history that she has given talks about it at events such as the University’s 2015 Festival of Teaching and Learning.

“I am not going to turn all my seminars into Lego workshops!” said Dr Cullum, a Principal Lecturer who specialises in medieval history, with a focus on religion and gender, “but I do intend to use it occasionally. The power of it is in the fact that it is something a bit different.”

Lego Serious Play is an established concept in the business world. And the University of Cambridge has announced proposals to create a post that the media instantly dubbed “Professor of Lego”. Endowed by the toy manufacturer, it would actually be the Lego Professorship of Play in Education, Development and Learning.

Serious Play

At the University of Huddersfield, Dr Cullum is a pioneer in the use of Lego as a teaching aid in the humanities. She decided to try it after she had attended a staff development workshop on Lego Serious Play.

“The idea is that the physical manipulation of something like Lego helps you to articulate what you are doing and helps you to express things using metaphors,” explained Dr Cullum.

“At the beginning of their courses, some history students find it difficult to move from concrete thoughts to more abstract kinds of thinking. So I wanted to see if using Lego in a seminar would help them moving from the concrete to the abstract, or from the practical to the verbal.”

Her opportunity came during a module dealing with the history of ideas. Students were reluctant to address the topic of gender.

Her opportunity came during a module dealing with the history of ideas. Students were reluctant to address the topic of gender.

“I thought they are either not interested or really struggling, so I thought I would try turning it into a game,” said Dr Cullum.

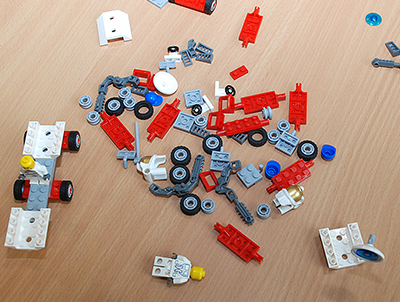

Teams of students were given Lego bricks and they explored ideas about gender by erecting structures such as a model of the Garden of Eden – with Adam closer to God and Eve ejected as the supposed sinner. There was even a World War Two scenario featuring a female French Resistance fighter. This led to a discussion of feminist philosophy espoused by the French thinker Simone de Beauvoir.

“It worked very well,” said Dr Cullum. “The students were really engaged and they all said how much they had enjoyed it. I cannot be absolutely sure that it improved their understanding, but I think that in some cases it did.

“Later on, I saw that significant numbers of them had chosen to do essays or exam questions on gender. Given that none of them had initially been interested, this shows that Lego had been a way to access the topic more successfully.”

“Gamification” is becoming an important aspect of education at all levels, added Dr Cullum.

“Making things enjoyable means it is easier for people to engage, and they will often do so longer and more deeply than if a subject is just something that they are expected to go away and learn. It is a way of helping people to learn more effectively.”