Letting the train take the strain

Wed, 14 Aug 2013 12:31:00 BST

The Steam Age meets the Neutron Age as train wheels take the strain

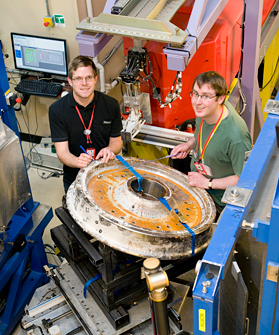

Pictured: ISIS users Robert Jones and David Crosbee, from the University of Huddersfield, using the ENGIN-X instrument to examine train bogie wheel, experiment RB1255011 at the ISIS facility, STFC's Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, 7th June 2013 (Credit: STFC).

Pictured: ISIS users Robert Jones and David Crosbee, from the University of Huddersfield, using the ENGIN-X instrument to examine train bogie wheel, experiment RB1255011 at the ISIS facility, STFC's Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, 7th June 2013 (Credit: STFC).

A group from the University of Huddersfield's Institute of Railway Research, led by Dr Adam Bevan, Head of Enterprise, has been using the ENGIN-X at ISIS to study new and used train wheels to understand how cracks begin and spread.

The ENGIN-X instument allows engineers the opportunity to test such large and heavy components such as train wheels rather than just metal samples.

The work has been undertaken at the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire and is being funded by a consortium including the Rail Safety and Standards Board, the Association of Train Operating Companies, Siemens, Lucchini, and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Every wheel on every train in the UK has to be replaced every five years or so and the maintenance and renewal of train wheels make up a significant proportion of the cost of our rolling stock. In everyday use the wheels are subjected to stresses and strains that can cause cracks to develop particularly in the wheel rims.

Every wheel on every train in the UK has to be replaced every five years or so and the maintenance and renewal of train wheels make up a significant proportion of the cost of our rolling stock. In everyday use the wheels are subjected to stresses and strains that can cause cracks to develop particularly in the wheel rims.

The manufacturing process of train wheels is designed to try and minimise the likelihood of cracks appearing. A process of heating and cooling the wheel hardens the rim and puts it under compressive strain, making it difficult for cracks to start.

However some cracking is inevitable and when these cracks have developed to a certain level the wheel is put on a lathe to remove the outer layer and any cracks that have formed. This exposes material underneath that is slightly less hardened, and can be more prone to cracking.

Dr Bevan explains: “We know that during operation, and during turning on the lathe, the stresses within the wheel also change. We’ve been involved in a major project with the Rail Safety and Standards Board to try and understand how, and what those changes mean. We know that the cracks grow more quickly toward the end of the wheel’s life, and this is true for various types of trains operating in different conditions. We wanted to know which was more important: the change in hardness or the change in residual stress. Hardness is easy to measure, but measuring the distribution of residual stress in the wheel is more difficult. Neutron diffraction allows us to measure several centimetres into the steel, and the big advantage of ENGIN-X at ISIS is the ability to test such large and heavy components.

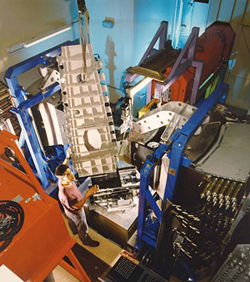

Pictured: A researcher working with the ENGIN-X at at the ISIS facility, STFC's Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (Credit: STFC).

Pictured: A researcher working with the ENGIN-X at at the ISIS facility, STFC's Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (Credit: STFC).

Dr Bevan continues: “We hope that our results will help people improve manufacturing techniques, optimise how they look after the wheels and also influence the choice of different materials. Siemens, who supply a lot of the UK rolling stock, and Lucchini, who manufacture the wheels, are co-funding the project in the hope of making cost savings without compromising on safety. Ultimately it could lead to a change in standards on how these wheels are manufactured and used.”

Sean Barson, Technical Services Manager at Lucchini UK in Manchester, said of the project: “We are always willing to support Universities in genuine new research such as this. We have extensive facilities in Italy but we don't have anything like ENGIN-X at ISIS. Collaboration between industry and academia can be beneficial and lead to improvements in safety and processes.”